Joint cartilage: the shock absorber in our joints

The cartilage in our joints performs a great service for us. In particular, it makes sure that we can move freely. The pressure-resistant connective tissue absorbs knocks and shocks and protects the joints when abrupt movements are performed. When the joint cartilage is healthy, it works like this: under load, fluid is forced out from the joint cartilage, and during rest phases it fills up again with fluid ready to cushion the next movements again. What is particularly impressive is that the joint cartilage can absorb the impact of five to seven times the weight of the body.

During our everyday lives, the six biggest joints are subjected to particularly high loads and stresses. These are the knee joints and the hip, shoulder, elbow and ankle joints. Depending on the joint, the cartilage in the joints has a thickness ranging from 0.5 to 5 millimetres. It consists of four layers and is coated and kept supple by joint fluid, the so-called synovial fluid.

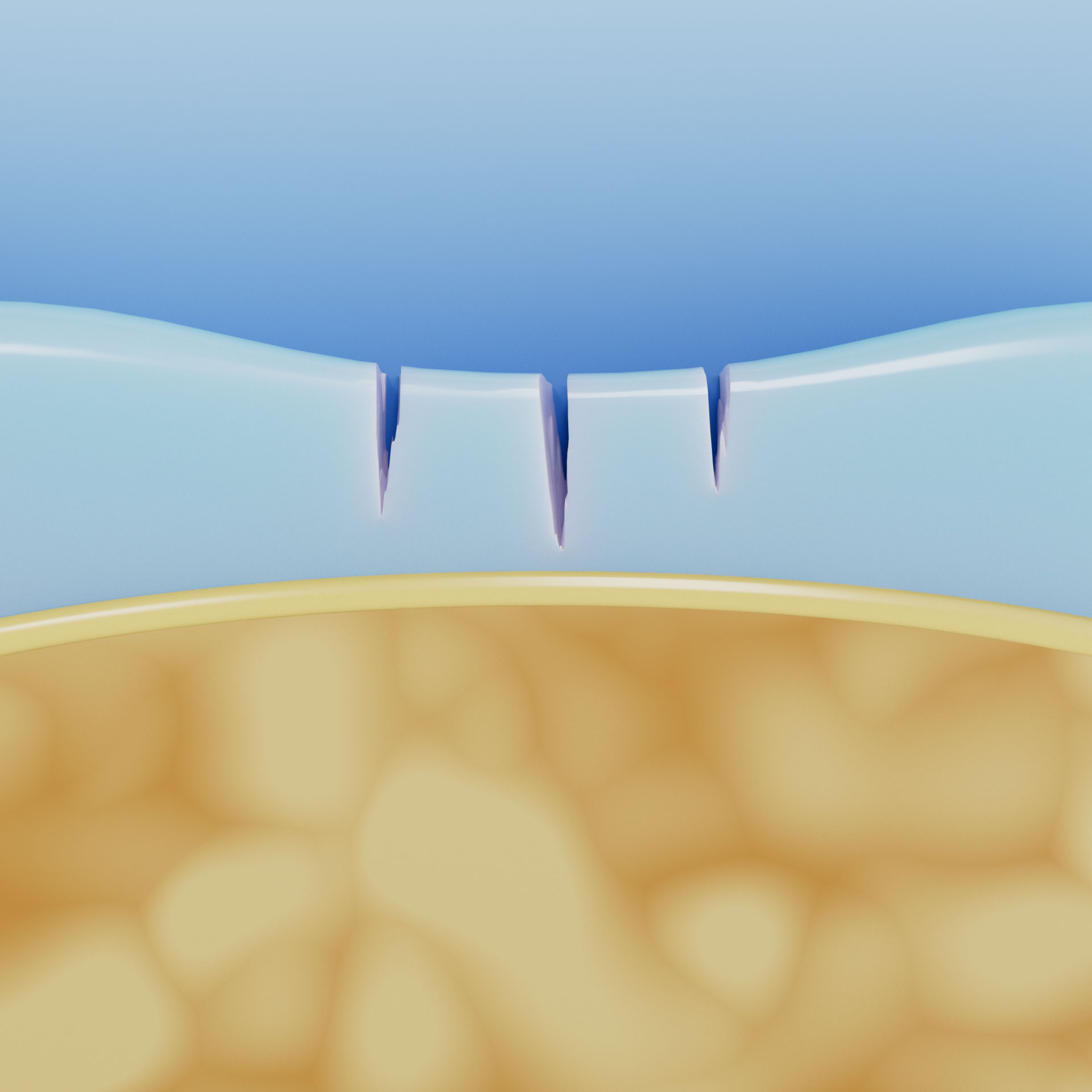

Based on the Greek word “Hyalos”, joint cartilage is medically referred to as hyaline cartilage, which expresses its blueish/white shimmering look and glass-like appearance. Joint cartilage consists largely of water and structural proteins, such as collagen and aggrecan. In comparison to other types of tissue, it contains very few cells and it is not supplied with blood. As a result, injuries or disorder-related changes to joint cartilage cannot generally heal by themselves.

Gradual wear and tear or sudden: how cartilage damage occurs

An unfortunate injury during sport, inappropriate stresses, circulatory disturbances, inflammation due to persistent severe obesity, lack of movement or simple ageing – the reasons for damage to joint cartilage can vary greatly.

Accidents and sports injuries normally occur spontaneously and can affect people of all age groups. Here, the acute cartilage damage is usually accompanied by painful associated injuries, such as ruptures of the cruciate ligament or meniscus, or injuries to the rotator cuffs of the shoulders. In addition, diseases such as osteochondrosis dissecans can lead to entire portions of the joint cartilage becoming detached in children and adults.

By contrast, cartilage damage that occurs due to wear and tear generally leads to gradual changes to the joint cartilage. The damage can progress so far that the surface of the cartilage is constantly eroded until, eventually, the subchondral bone underneath is exposed. If this stage is reached over a larger area then only an artificial joint replacement can preserve the mobility of the joint. This tends to affect older people and people who have a persistently unhealthy lifestyle. Chronic diseases such as rheumatism, gout and osteoporosis can also lead to cartilage damage over time.

As a result, five million patients suffer cartilage damage on their knee joints alone every year. Other joints like the shoulders and ankles can also be affected.

Diagnosis and degrees of severity of cartilage damage

If every movement hurts and the joints are aching, then it is high time to go to the doctor and get a check-up.

Because joint cartilage does not generally regenerate itself, it is important that it is treated early on if injuries occur. If this does not happen then there is a risk of follow-up damage, including premature onset of arthrosis or, ultimately, also the need for an artificial joint.

The orthopaedic doctor will take down the medical history of the patient and use this to investigate the reasons for the knee pain or the pain in other joints. The doctor will use imaging techniques to gain an accurate understanding of the affected joint. An X-ray is normally used to check for fractures or bone changes that appear e.g. if arthrosis is present. However, joint cartilage itself cannot be seen on an X-ray. Instead, this is possible with high-resolution magnetic resonance tomography (MRT). However, in order to gain the most accurate possible picture of what is going on in terms of the cartilage damage, an arthroscopy of the joint is needed.

Classification of the International Cartilage Research Society, ICRS

If cartilage damage is determined, this is classified into different grades depending on severity:

- Grade 0: No defects evident

- Grade 1: Intact cartilage surface, slight softening of the cartilage with superficial tears

- Grade 2: Cartilage damage to < 50% of the cartilage depth (abnormal cartilage)

- Grade 3: Cartilage damage to > 50% of the cartilage depth

- Grade 4: Cartilage layer missing, subchondral bone is exposed and already displaying damage (arthrosis)

Cartilage damage grade 1

Cartilage damage grade 2

Cartilage damage grade 3